This is not intended as a review. I’m going to discuss the game design in Tunic from my perspective, informed by my own biases and projection about what I think the designers intended. This is not meant to be a critique either. It’s more of a compilation of some salient aspects of the game design in my opinion. Minor spoilers ahead, so if that concerns you, then maybe come back later, I’ll be here.

By and large, much of the progression in Tunic is gated by the player’s intuition. With nothing more than a partially complete in-game instruction manual written largely in an inscrutable language, you need to “read between the lines” and suss out what to do next. It often feels similar to the experience of an escape room, where the player must take in a large amount of unclear information and “find the needle in the haystack”.

The in-game instruction manual is a huge design achievement in my eyes. It needed to not only look and feel like a holistic instruction manual, it also needed to be drip fed to the player page by page in a way that the new information could implicitly guide the development of their horizon of intent1 throughout the game. There are many pages that have information to proceed on one side, and the setup or punchline for narrative development on the other. Sometimes both on the same side!

The instruction booklet also serves a role of delivering exposition to the player, which manages to feel rewarding all on its own thanks to how opaque the game’s narrative and aesthetic can feel. You know you’ve set up a compelling system when players are thirsty for more exposition.

The booklet is distributed to be the true “progression” in the game. The player could technically sequence break at any time due to the game’s reliance on what I’ll call “knowledge gating”. As you play, you will find yourself coming out of odd corners of the isometric view that lead back to a familiar area. Or you will reach new areas with abilities you started with. This drives home the point that “I could have done that the whole time!”.

Tunic struck me with a sense that it was designed with Speedrunning in mind. There’s a second, “secret” sword that you can unlock late in the game with the “Holy Cross”. On a causal play through, it’s pointless as you already got a sword many hours before, but it implicitly proclaims the possibility of getting to the west gate immediately from the beginning.

One could also spawn items at any time if they knew how, or one could simply navigate through the dark caves blind if they knew the path. The heavy use of knowledge gating drives home the notion that the game can be engaged with in a radically different way if you knew what you were doing ahead of time.

As a speedrunner in a past life, I appreciate it. I would argue that actively opening the door to that kind of open-ended play greatly increases the long-term value of the game, keeping it interesting for players as long as they want to engage with it. Even if one wasn’t interested in speedrunning per se, it engineers a powerful experience of seeing the game’s world from a different perspective.

Games are one of those artistic mediums that I think are particularly adept at creating the experience of profound recontextualization, so it’s always exciting to see a game go out of its way to do so.

Items in Tunic follow in the footsteps of the instruction booklet’s commitment to hiding information and creating an intuition-heavy play space. It’s coy about basic things like what an item does (or even what it’s called)! This gets the player quickly conditioned to simply try things and see what happens.

What is particularly interesting to me about the items though, is that they are all finite in usage (very finite, you tend to only have 1 or 2 of a given item in practice) and they don’t come back when you die. That design decision on its own tends to lead players to hoarding items for a rainy day. But when you don’t even know what a given item does, you can’t accurately hoard, so you are encouraged to try to use everything at least once.

The kicker is that if you use the items liberally, you will be rewarded with extras of the given item that refill on each death. I really like this idea and find that in practice, it allows the game to have real tension when deciding whether to use items while encouraging the player to use them liberally without resorting to “use it or lose it” mechanics commonly used in other games that attempt to counter the hoarding mentality.

Granted, some players may find that this was ineffective at countering their tendency to hoard, given the fact that none of the expendable items are strictly required for progress. Your mileage may vary, but I thought it was a creative solution and gave an interesting new dimension to the play space as to whether or not you should use an item.

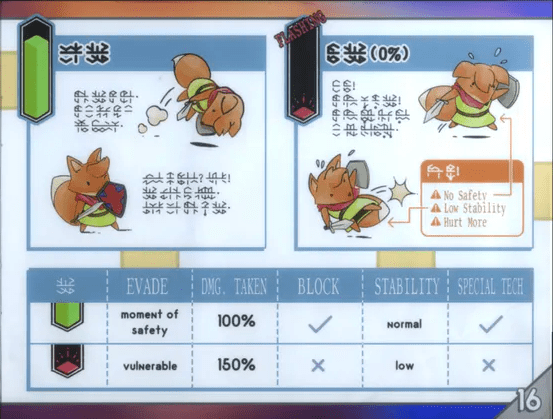

One of my favorite combat mechanics is the “Exhausted Dash”. It allows the player to continue to dash at the same speed as before when running out of stamina at the cost of not being invincible and taking extra damage while tired.

This opens up a dimension of risk-reward to the fundamental mechanics. One can use this dash to keep speed up when running from enemies, but it eventually forces the player to stop and catch their breath. Given how persistent enemies are in the game, this often leads to situations where the player will get surrounded and overwhelmed.

The Siege Engine boss (video of boss fight) feels designed to maximize the aesthetic of danger and risk from this exhausted dash mechanic. Initially, a player would likely default to trying to keep their distance from the boss (its huge after all). However, the boss has several attacks that hit a wide area in front of it, such as a powerful sweeping laser and a long-lasting tracking attack.

The player will likely find that in practice, the tracking attack is too accurate and lasts too long to dodge it from range, and there isn’t enough cover to wait it out. Ultimately, the player is encouraged to get as close as possible and hit the boss from behind.

Once they commit to this strategy, the boss starts jumping around in as if to say “get off me!”. Practically speaking, in order to stay behind the boss, the player is going to have to dash until they are out of stamina constantly.

For me, the fight turned into a desperate pursuit, constantly using the exhausted dash on cooldown just to keep up. It was amazing! I found myself blurting out “keep running little guy!”. I really like how the game encourages this experience through the dynamics of how the boss and gameplay mechanics interact. Perhaps some may not have had the same experience with the boss as I did, but it seems pretty clear to me that it was designed to create these kinds of situations.

Some combat options seem to be not very useful in practice. Some clear examples are the freezing mechanic and the shield’s parry.

You are given two ways to freeze: expendable potions and a magic item. The former has limited usage and the later has very high startup. These drawbacks would be fine if landing the freeze was rewarding. But in practice, you can only get one or two slices of your sword before the enemy is freed. The same issue applies to the shield parry, it has very long startup and end lag, where the only reward is at most two slices.

There isn’t any kind of long startup, powerful attack (like a stab or jump attack) that would allow you to capitalize on these openings, and as a result makes the freezing and parry mechanic feel ineffective.

One thing that stuck out to me, was the way that Tunic handled it’s RPG-style leveling mechanics. Personally, I’m a bit of an extremist with regards to RPG leveling mechanics and dislike how they reward players for grinding. I feel this undermines the game’s experience for everyone whether or not you choose to engage in the grinding. So I must admit I rolled my eyes when I realized this game has a level-up mechanic. That said, I think Tunic manages to bypass the grinding problem well.

The player is given items that can be redeemed for level-ups using the coins you get from combat. This simultaneously manages to reward the player for fighting well (not dying and losing your coins), exploring well (finding the items in the first place), and also limiting how powerful the player can become due to each item’s scarcity.

I see this as a drastic improvement over a simple additive XP system. The player is not incentivized to grind, keeping the balance of the game in check, while allowing for a certain degree of freedom for players to level up for challenging fights if they so choose.

Near the end of the game, the player will become a ghost and lose all of their levels in the process. I love this!2 For the final act of the game, you are given the chance to show how far you have come. This confirms to me the developer’s commitment to keeping the leveling mechanics in check.

Tunic’s a lot more than the simple nostalgia trip for Legend of Zelda that it may seem on the surface. It utilizes design ideas both classic and modern, and polishes them to an impressive degree, making a complete system that is far more than the sum of its parts.

Footnotes

- “Horizon of Intent” here was popularized in Brian Upton’s book “The Aesthetic of Play” and refers to the subset of actions that a player considers worth doing in a game at any given moment. Managing, understanding, and cultivating this horizon is arguably a core essence of game design.

- I’m the kind of player who loves games willing to “hurt me plenty”. I consider this ramp up in mechanical challenge a feature, not a bug. Your mileage may vary.